Like a soldier going into battle for the first time, being my mother’s caregiver for the final nine years of her life was a baptism by fire for me. My mother and I learned so much useful information through those years that she made me promise I would write a book about what we learned. I was so gratified when someone told me that Making Peace with Death and Dying it should be a reference book in every home. Here are the top five things I learned about dealing with death:

1. Don’t assume you are supposed to know what to do.

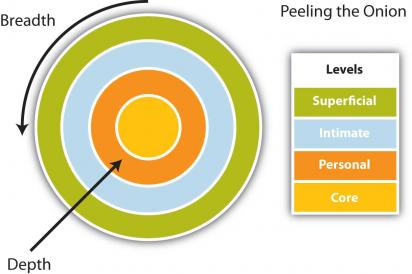

We live in a death-denying culture that has a hard time even saying the word “death.” We are not taught how to face our own death or that of a loved one. It is therefore no surprise that many of us panic in death’s presence. At the very least, it is common to be ill at ease. We don’t know what to do or not do.

So, remember it is normal to be ill-prepared to face death – your own or that of a loved one. Recognize this state of affairs. Don’t pressure yourself to “do it right.” When someone you love is dying, it’s okay to be a mess. Just try not to dump your mess on others — especially the one who is dying.

No two people are going to respond the same way to a death. Most will be woefully unprepared and unskilled at dealing with the situation. This will not, however, stop some from shirking their responsibility or being self-appointed bullies demanding that others follow their lead.

The best approach is to lead with your heart. Keep your love flowing with the dying person and others as well — if possible. Nothing is more important than loving each other. Do your best and then some.

2. Make it a priority to demonstrate your love for the person who is dying.

The fact that your loved one is dying can be overwhelming and scary. Do your best not to let that get in the way of keeping your love alive. You are there to see them off on their journey into the unknown territory of death. Love them up, down and sideways, but don’t make a big deal about it. Just let your love flow and watch for little things that you can do to be of service to them.

Accept the reality if a loved one is dying. Don’t try to deny it by saying things like, “Your color looks good today” when you both know he or she is dying. That’s like saying “I can’t handle this and need to pretend it isn’t happening.” Be honest. Be authentic. Be you. It’s okay to let them see your fear and distress, but don’t let that overshadow your love.

Express your gratitude to the dying person for the ways they enriched your life. Share happy memories and yes, do say goodbye — but do it tenderly. Don’t be afraid to touch the dying. Nothing communicates our love more than a loving touch. Hold their hand. Stroke their hair.

Tailor your efforts according to the time available. Respect the fact that time can be very short from hearing the prognosis to the actual time of death. One of my personal pet peeves is when people are inconvenienced by the news of a loved one’s impending death. They act as though their loved one should have checked on their availability rather than having the audacity to sound the red alert at an inopportune moment. When your mother has a 50/50 chance of making it through the night, you don’t show up four days later!

3. Respect the authority of the dying to make his or her own decisions.

The person who is dying is the boss. If they are conscious enough to be making their own decisions — don’t bully them into doing things your way. Just as sure as you are that your way is right for you, know that their way is right for them no matter how different it is from your own. If someone holding a healthcare proxy is in charge, respect his or her authority.

Ideally, each of us gets our ducks in a row before our dying time. In reality, most do not. As a result, a lot of financial, legal, physical, mental, emotional and spiritual life-or-death decisions get made in a hurry, at the last minute. This can cause a lot of chaos, confusion, conflict and mixed up emotions among family and loved ones. Do your best to quickly align yourself with the wishes of the dying. It is their death, not yours.

4. Accept that he or she is dying. Don’t fight against it.

It’s fine to hope that things will turn around and death will be postponed. However, if death is what is happening, it helps enormously to accept that fact. We are taught to fight against death like it is an evil monster. In fact, death is as normal as birth — we just haven’t been trained to see it that way. I find it sad when doctors and loved ones subject the dying to endless invasive drugs, tests and procedures when it is obvious that it is time to die. I am an enthusiastic supporter of hospice care for the dying.

Each of us is born one moment of one day, we die one moment of another day and have an unknown number of days to live in between.

Make the most of the time you and your loved one have left together. Fill it with tenderness and be of loving service to their wishes and needs. Give them a good send off.

5. Contribute to maintaining a peaceful environment.

When someone is dying, they have enough to do handling their own process. They might be dealing with physical pain, fear, emotional turmoil, confusion, regrets, etc. Assume that any discord in their environment will add to their load and be unkind on the part of those causing it.

Even if the dying person is seemingly unconscious, assume he or she can hear and be affected by everything that happens around them.

If family members are squabbling, take it outside of the room. Consider the dying room a sacred space where only love and comforting activities are allowed unless the dying person requests otherwise.

Give your loved one the best send off possible leaving no regrets.

If you would like to know more about me and my work, please explore my website here.