Advance Healthcare Planning Part 2:

Why Filling Out Your Forms is Not Enough

In Part One of this article, I discussed why every mentally-competent individual over the age of 18 needs to have advance healthcare plans in place. Here we will look at the in’s and out’s of how to make sure your plans will be able to be put into effect when the time comes. To put the importance of Advance Healthcare Planning (AHP) into perspective, consider the following facts:

• Doctors are trained to preserve and save lives and for many it is difficult and sometimes considered a professional failure to broach the subject of death and referral to palliative care or Hospice services rather than to suggest yet another treatment with slim possibilities of helping the patient to recover.

• According to the Center for Disease Control the vast majority of Americans say they want to die at home, but 75% die in a hospital or nursing home.

• Almost 1/3 of Americans see 10 or more doctors in the last 6 months of their life, most dying in the ICU. (Source: Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare, 2005)

• In 2009, Medicare paid $55 billion just for doctor and hospital bills for the last two months of patients’ lives. That’s more than the budget for the Department of Homeland Security or the Department of Education. It’s been estimated that 20-30% of these medical expenses may have had no meaningful impact. Most of these bills were paid by the Federal government with few or no questions asked. (Source: The Cost of Dying, 60 Minutes, 8/8/10)

As mentioned, most of us who have even filled out our Advance Healthcare Directives, are woefully in the dark about some very important aspects of how this all works. Basically, filling out the forms simply isn’t enough. That’s only one of five critically important things you have to do to ensure that whoever you appoint as your Healthcare Proxy will be able to speak competently on your behalf if, and when, you cannot speak for yourself. The five key things you need to do are:

1. Educate Yourself and Others: Before you fill out any forms, educate yourself about all the terms and nuances involved. Understand the purpose of each form as well as what it can and cannot do. Here are some fundamental points you should be aware of:

• A Healthcare Proxy is a legal document. It can be overridden by either a revised form or by your spoken word (when conscious and mentally competent). Your proxy is only called upon if and when important healthcare decisions need to be made and you are unable to do so for yourself. This means, anytime you are having surgery and being anesthetized, are unconscious briefly or for an extended period of time, or are declared mentally incompetent to speak for yourself. If you don’t have this form filled out in advance of need, then you forfeit the opportunity to exercise your right to choose a spokesperson.

• Remember, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, 28% of us die before reaching the age of 65 – so do yourself and your family a great service by educating yourself and them about Advance Healthcare Planning.

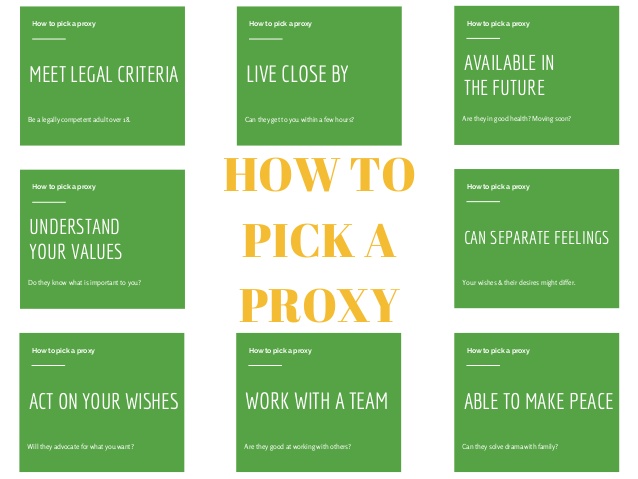

• When selecting your healthcare proxy and alternate proxy, your obvious choice is often not the right one. Don’t worry about offending anyone for not choosing them, but be sure to explain to them why you made another choice. For example, my brother was my obvious choice, but when I reflected on how hard it was for him to be around our mother when she was dying, I realized how hard it would be for him to serve me in that way and chose someone else, but have made sure he will be well-informed and able to just focus on being my loving brother. Other than the legal criteria spelled out by your state laws, consider the following in choosing your proxy. Pick someone who:

• Knows you well and will respect your wishes and needs even if they would make different personal choices.

• Can provide a safe emotional space to share your thoughts and feelings without imposing theirs on you.

• Will be able to take care of him or herself while serving in this capacity for you.

• Will support your needs even when the going gets tough.

• Will be able to speak up to doctors and caregivers to be sure your wishes are honored.

• Will stay informed of your condition and be available to make important decisions.

• Is likely to be available in the future. For example, does he/she live close by? If not, will they come if needed?

• Will be able to be assertive in handling potential conflicts between your family, friends, doctors, and/or caregivers?

• A Living Will is not always considered a legal document, but is intended to provide clear and convincing evidence of your wishes regarding care and treatment in the event that you are deemed to have no reasonable expectation of recovery. The purpose of a living will is to exercise your right to instruct your doctors and caregivers to withhold or withdraw treatments that would simply prolong your life under such conditions and to focus instead of keeping you comfortable and pain-free. Specific treatments that are often withheld or withdrawn are:

• Cardiac Resuscitation (CPR) is a group of treatments used when someone’s heart and/or breathing ceases. CPR attempts to restart the heart and breathing through mouth-to-mouth breathing, pressing on the chest to circulate the blood, electric shock, and/or drugs to stimulate the heart. When used quickly in response to a sudden event like a heart attack or drowning, it can be life saving. However, if someone has stopped breathing for more that 4-6 minutes lack of oxygen to the brain may lead to brain damage. It is important to realize that the success rate for CPR is extremely low for people at the end of a terminal disease process – especially for the elderly where successful CPR, if achieved at all, is seldom sustainable and often results in broken ribs.

• Mechanical Respiration involves inserting a tube through the nose or mouth and into the windpipe, forcing air into the lungs. For the dying patient, mechanical ventilation often merely prolongs the dying process until some other body system fails. It can supply oxygen, but it cannot improve the underlying condition.

• Artificial Nutrition and Hydration can save one’s life by supplementing or replacing ordinary eating and drinking when used while the body is healing. It can also be used long-term for those with serious intestinal disorders or an irreversible and end-stage condition. Withdrawing artificial nutrition and hydration does not cause starvation or pain to the patient and no legal or ethical issues exist when this is done in accordance with the patient’s wishes. It is the underlying disease and NOT the withdrawal of treatment that causes death.

• Antibiotics are often used in hospitals and other healthcare facilities where elderly and terminally ill patients are often vulnerable to contagious and opportunistic infections. Antibiotics tend to weaken the immune system and make the patient susceptible to other infections and a downward spiral of one infection and antibiotic after another.

• Maximum Pain Relief, including the use of narcotic medications for the terminally ill patient is considered by many to be truly compassionate and humane. It is indeed for this purpose that these medications exist because they enable doctors to effectively treat most pain and keep the patient comfortable.

2. Fill Out Your Forms: As mentioned in Part 1 of this article, there are lots of wonderful websites to consult about the in’s and out’s of Advance Healthcare Planning. For the state of New York, for example, I recommend going to Excellus BlueCross BlueShield to view their Advance Care Planning booklet which can be downloaded from their site. Similar sites exist for all states and provide detailed explanations of the in’s and out’s of Advance Healthcare Planning and provide the state’s forms.

3. Communicate Effectively

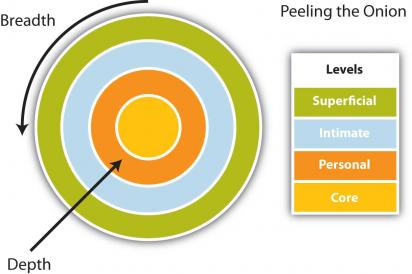

Talk to your healthcare proxy, family, loved ones, and doctors about the specifics of your wishes regarding end-of-life care. Don’t be surprised if they resist and/or insist they don’t want to talk about things like that. Ask them to listen for you because it is important to you and because you do not want any squabbling or misunderstanding over your wishes regarding care and your choice of a Healthcare Proxy.

4. Distribute and Enforce: Plain and simple – what good are your forms if no one knows where they are or what they say? You need to know where your forms are and you need to make copies and distribute them to your doctor(s), proxy and alternate proxy, and bring a copy when being admitted to the hospital or having a same day surgery – in other words, any time you might be put under anesthesia. Get a business card-size proxy form for your wallet. There is one, for example, that can be used for anyone from any state at the end of the Excellus BlueCross Blue Shield Advance Care Planning booklet mentioned in #2 above. Also, keep a copy of your proxy and Living Will in the glove compartment of your car and bring them with you whenever traveling – especially overseas.

5. Review Your Decisions at Least Each Year: When looking over your forms each year, be sure to check online to find out if there have been any changes in your state’s laws regarding AHP. If so, review those to be sure your forms and understanding of the laws are up to date. If needed, redo your forms and redistribute them as discussed in #4 above. Each year and whenever there is a major change such as a change in the law or a new medical treatment option that might affect your choices or you receive a terminal diagnosis, have a change of marital status, relationship, or a change of heart review your Healthcare Proxy and Living Will to be sure they remain an accurate reflection of your wishes.

Advance Healthcare Planning is your right, but it is your responsibility to get in the driver’s seat and exercise that right. That is not a one-time thing. Circumstances change and so do our minds. Pay attention and take care of your precious self so others can take care of you according to your wishes if such a time comes.

Please circulate this article among your social network – it might save someone’s life or at least save them from a lot of heartbreak.