Steve Jobs’ last words, spoken with great delight, were, “Oh wow! Oh wow! Oh wow!” What was he seeing? Perhaps what those returning from near-death experiences consistently report — a sense of moving through a dark tunnel beckoned by a compelling bright light, feelings of peace and well-being, the knowledge of being outside of the body, what some call an intense feeling of unconditional love, and encounters with beings of light. This piercing of the veil of “the other side” unwaveringly suggests that “passing over” is a beautiful experience.

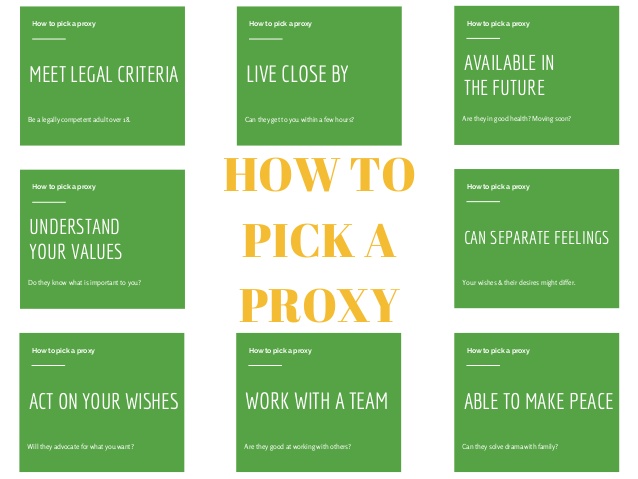

In stark contrast to these images, we live with a cultural consciousness about death that personifies it as “the Grim Reaper” or “the Angel of Death.” Not knowing when or how our time will come, many live in fear of the unknown and uncontrollable aspects of death with a sense of a foreboding encounter with darkness and evil. Nowhere is this more vividly demonstrated than in an Internet image search of the word “death” that yields haunting black-and-white images of skulls, crossbones, and the Grim Reaper. I encourage you to take a moment and do an image search now. These portrayals demonstrate the power of the death taboo on both our conscious and unconscious awareness.

Among the top 10 images, several date back to artwork from the 1300s during the Black Plague when half the European population was wiped out. The plague was considered a form of punishment by God. Symbolically representing death — with depictions of skeletons, skulls, and crossbones — was a common way of mocking it in order to reduce feelings of helplessness and anxiety. People wore these death symbols on their clothing as a way to fool Death into thinking that they had already been touched and should therefore be left alone. If these images are indeed a valid reflection of the collective consciousness about death today, it is no wonder that so many live in fear of death and treat it like the unspeakable elephant in the room.

As children, we could run to the comfort of our parents with our fears. It is a sad commentary on our society that as adults so many of us silence and suppress our own fears about death’s unknowns, concern about unmanageable pain, the loss of control over one’s own life, and the possibility of being isolated from loved ones at life’s end. Rather than sharing our beliefs, thoughts, fears, and concerns about dying and death, we suffer in silence having no idea how to wrap our brains around the reality of death or to even broach the subject with our loved ones or doctors. Far too many of us, including terminally ill patients, put a smile on our face and silently suffer in emotional isolation. The death taboo interferes with our ability to have a healthy relationship with death.

The good news is that since the 1960s, momentum has been building to transform our culture of death. Among the most apparent changes and influences:

- Beginning in the late 1950s, the conversation about human mortality and the American culture of death moved from academia and religious institutions to the general public — raising the topic from our unconscious to conscious minds.

- The hospice movement came to the U.S. in the 1970s, exposing the dying and their families to healthier role models of how to relate to death.

- The sharing of accounts of near-death experiences in popular literature began in the mid-70s, consistently offering beautiful new images of death.

- Philanthropic funding led by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and George Soros’ Open Society Foundation began in the 1980s, and focused on changing theculture of death in America through legislation, public engagement, and changes in the fundamental philosophy of death in the professional education of doctors and nurses.

- In 2011, the 79 million baby boomers began turning 65 at a rate of 10,000 each day. This will continue for another 17 years.

- A 2009 Newsweek poll estimated that 93 million Americans (30 percent) self-identify as “spiritual but not religious,” saying they are deeply spiritual but claim no specific religious affiliations. This group has doubled in size in the past decade and is a driving force of change in social rituals around birth, marriage, and death that are not rooted in religious doctrines.

Buoyed by the confluence of these forces, this is an exciting historical moment where matters of our beliefs and values regarding life and death are concerned. Both culturally and individually, we have a great opportunity to rethink our most fundamental definitions of “birth” and “death.” Our physical and spiritual understanding of these terms must be reconciled in the process. Here are some questions to ponder:

- When does life start and when does it end?

- Are these terms specific to the physical beginning and ending of life or are there other dimensions of our existence that precede and follow what we commonly refer to as a lifespan?

- Is the physical birth and death and lifespan of an individual all there is?

- Or, is there more than meets our eyes?

- Is the start of life “good” and the end “bad” as reflected in current social attitudes?

- Or, is this a matter of interpretation?

- How does the fact that the personhood you commonly know as yourself will die inform the way you live your life?

- When a loved one is dying, are you able to bring your authentic self to the situation and be a comfort, helper, and to communicate your loving fearlessly?

Never has there been a time when we had a greater opportunity to reevaluate our beliefs and values regarding life and death and to hold ourselves accountable for the quality of our relationship to both. Let’s talk about this. Please share your thoughts below.