No doubt, most of us, if given the choice, would prefer to die peacefully in our sleep with no unfinished business with ourselves or others. This we call “a good death.” But it is important to look below the surface of this idea to understand its misconceptions.

The culture of death in the United States is beginning to get a much needed renovation. We have all been brainwashed for far too long by a death taboo that immigrated to our shores from Europe and has dominated our conception of death ever since. In my upcoming book, Shining Light on Dying and Death, I explain the causes, dynamics, and consequences of this death taboo and how it has handicapped us from having a healthy relationship with death. Readers are then engaged in a process that gets them out from under its influence.

Consider the following images representative of an Internet image search of the word, “Death.”

Notice that they are black and white images of skulls, skeletons, crossbones, and the Grim Reaper. These images originated in the 1300s in Europe when the Black Plague wiped out 50 percent of the population. They were sketched by people then who pinned them to their clothing in an effort to fool Death into passing over them, thinking they were already dead. What kind of feelings do these images evoke in you? For most, it is the kind of fear that makes us avoid death “like the plague.” Yet, no one gets out of here alive. When we run away from those things we find uncomfortable or are downright terrified of, we never learn how to face our fears and strengthen our capacity to move through the trials and tribulations that simply come with the territory of being alive.

This avoidance of death has evolved into a resistance to all forms of pain and suffering and the illusion that a “good” life or a “good” death is devoid of suffering. Yet, if we stop to think about it, some of the greatest treasures of our lives have come through some form of suffering. Our pain and suffering often draw us closer to one another giving us the opportunity to demonstrate and deepen our love through acts of compassion, kindness, and caring. In order to meet our life’s challenges, we enter into them rather than running away from them and find that we are strengthened and learn to build our character and fortitude.

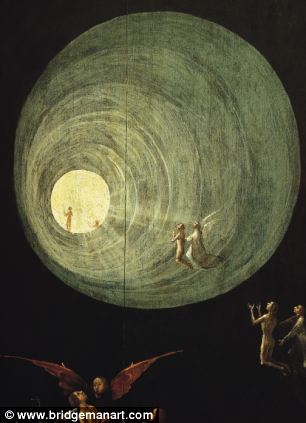

There are other ways of seeing death that reflect a different kind of relationship to dying and death and thus an alternative response to fear. Consider this set of images from an Internet search of the phrase “Near Death Experience.”

What do these images suggest? What kind of feelings do they evoke in you? Notice the hint of pastel colors, the beckoning light, and the sense of some part of us rising up from our dead body. These images also suggest the unknown or unknowable quality of death, but not in a fearful way. It is more of a sense of transition into something or somewhere else. If you live in fear of death, consider the possibility of what it would feel like had you been “brainwashed” with images like these.

Another consideration contrasting these two sets of images is that the “Death” images imply that death is the opposite of life – ie you are either alive or dead. The “Near Death Experience” images suggest a cycle of transformation where death is the opposite of birth, set apart by life. In other words, “we” are born, we live, we die, we are reborn, we live, we die, etc. It is interesting to note that when I first did this image comparison about six years ago, there was no overlap of these images. Yet, today, I found images of moving into a tunnel of light among the “Death” images. This is new and encouraging news about our renovation of the culture of death in America.

If we are more open-minded and have a healthier concept of death, then we are likely to also have a far different way of responding to suffering. Some believe that suffering can be better understood within the context of karmic accretions (both positive and negative) from the past (both within this life and previous incarnations) that are being balanced as we experience the fullness of life. In this understanding, we are not so concerned with what looks and feels good as with what is beneficial and productive to our journey through life. There is an implication that we are doing some kind of important inner work that belies the understanding of our small, personality selves.

Looking at the pain and suffering of living and dying within this context suggests that a “good death” for example might not be the one that looks peaceful and isn’t messy, but rather the one that accomplishes what that soul needed to have happen to complete its work in this lifetime. For some, this might be attractive, while for others it might be extremely difficult to endure or bear witness to. Who are we to judge? Being open to the fullness of living and dying allows us to take advantage what life has to offer and as Mavis Leyrer advises, “Life’s journey is not to arrive at the grave safely, in a well preserved body, but rather to skid in sideways, totally worn out, shouting ‘Holy shit, what a ride!'”

If you would like to know more about me and my work, please explore my website here.

Also, if you know anyone who might get value from this article please email or retweet it or share it on Facebook.